“… world housing shortage” … “ … WORLD HOUSING SHORTAGE ! ? ” following the rich experience of moving through Barbican’s ‘Constructing worlds, Photography and Architecture in the Modern Age’ exhibition it’s these three little words that jump out of a wall caption, determining just how you will begin your written response to the show.

Guy Tillim, Grande Hotel, Beira, Mozambique, 2008

Here, in the photographs of Guy Tillim, Iwan Baan, Bas Princen and Walker Evans we repeatedly encounter a vacuum of abandoned, poor and makeshift buildings avidly filled by the nature of peoples’ fundamental needs; people motivated, not by profit and speculation, luxury, desire or competitive aspiration but by sheer, basic survival. Surely then a ‘world housing shortage’ must be unnatural, and if it doesn’t arise from nature then where does it come from? We can only assume it is from capitalism, rarifying, strategically as it does, supplies of resources essential for life that it has unnaturally commandeered, enclosed and monopolised for its own accumulative purposes, thereby denying to millions fundamental needs and rights.

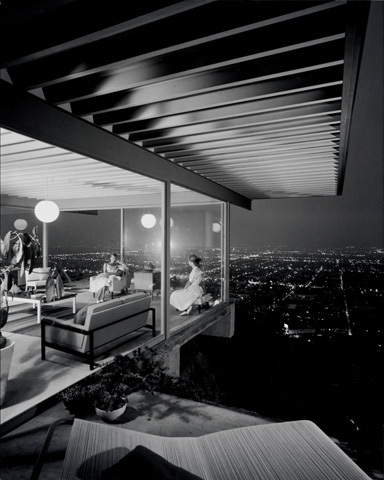

Julius Shulman, Case Study House #22, Stahl House, 1960

Dwelling, a concept that was close to the heart of Martin Heidegger, is repeatedly associated here with dreams. From the impoverished shacks and humble towns recorded by Evans in the 1930s (and into which advertising already asserts itself like its very own force of nature) to a Le Courboisean masterpiece rendered Surreal, as if smudged from charcoal, by Hiroshi Sugimoto, and on to the gutted wreck of the Congo’s ‘Grande Hotel’ photographed by Tillim and the cocktail-sipping eyries, cantilevered artfully over L.A and photographed as supreme objects of bourgeois desire by Julius Shulman, you consistently see how capitalism turns necessity into dream by means of that famous ‘conjuring trick’ exposed and explained by Karl Marx in the first chapter of his best known tome. Surely there is no ‘world housing shortage’, or at least no good reason in this world for one, other than according to the particular, unnatural and inhuman reason of capitalism itself.

Thus the land and its minerals are claimed, annexed and exploited for profit by people living extremely different lives to the actual excavators and far removed from the impoverished lands out of which wealth is extracted. Food and water too are colonised, claimed and exploited for profit by this same, particular and historical economic system, which is unlike communism or socialism, and unlike other economic systems mankind has known, such as that of the Native American Indian or the Australian Aborigine.

Left to their own devices, the diminutive human figures we often glimpse within this unarguably magnificent display of photography tend to solve the basic problem of shelter as best they can, given that their own unnatural predicament is to exist at the bottom or on the margins of an economic system within which they find it difficult to participate, contend and survive. Their solutions are never the outcome of guidance or assistance from market, law, or government; they exist at the bottom and on the margin of all such forces and institutions.

Lucien Hervé’, Documents of Le Courboiser’s Chandigarh, 1955-61

The flipside to receiving such harrowing reminders of social inequality, delivered in the specially dry, clipped tone in which photography speaks, is the seductive formal spectacle of modern architecture’s special affinity with modern photography (perhaps, in some carefully researched revision, you might prove their innate contingency.) Again and again we see viewfinder and print framing a harmonious composition of geometries and grids, lights and shadows, colours, planes and volumes all conspiring in apparently effortless syntheses. Lucien Hervé’s documents of Le Courboiser’s Chandigarh provide the apotheosis of this pervasive tendency. Museum-scale prints, lovingly prepared and presented by the artists, printers and curators explore the widest range of hues and tints, featuring a pastel wash here, stark chiaroscuro there and taking you from the stained-glass vivacity of Iwan Baan to the pale, rococo finesse of Luigi Ghirri, so that, for a moment you harbour the foolish notion that photography is capable of doing anything that painting can do.

Of course, there is a social and ethical aspect to modern aesthetics too as form follows, not only function but also affordability, budget and profit, the classic example being the clever extrusion of a relatively small, disused lot into – Hey Presto! – a huge tower that multiplies any initial investment by the maximum number of identical floors that can be stacked upon it.

Given the endlessly excessive availability of space so easily and readily found for businesses and offices; for property portfolios racked up by tycoons; for 30-bedroom mansions lavished on the pampered egos of barons and billionaires, and the acres of robust industrial buildings lying empty in and around our cities, it is difficult to comprehend ‘housing shortages’ on even a local or national scale. When the issue is raised to a global level it becomes more clearly unacceptable and unavailable for justification or comprehension. Any ‘housing shortage’ is always, and surely, the outcome, not of nature, nor of ignorance, but simply of greed.

I really enjoyed this writing but I wondered, if capitalism didn’t organise capital, then how would we ever have the benefit of “geometries and grids, lights and shadows, colours, planes and volumes”. Couldn’t capitalism be looked at this way: the capitalists have vision beyond their own needs, they then need to find funding for that vision. Knowing nothing about anything, I wondered why that version isn’t true.

LikeLike

.. the function of capitalism is to falsely create scarcity and thus create value from which they profit. In the case of essential needs such as housing untrammelled capitalism has created havoc to every corner of human endeavour, it has been the very mechanism which has been the gambling chip which brought down the economic function ability of society.

To invest and develop, to see the potential in the spaces we live as potent and expressive are not necessarily dependant on random philanthropy, but may form part of civil progress drawing in all partners.

Thank you again Paul.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great piece Paul. Many Thanks

LikeLike